Turkish Traditional Archery – Part 2Turkish Traditional Archery Part 2: Technique and Tackle Murat Özveri, DDS, PhD The tracks of Turkish traditional archery can be followed from the western coasts of Anatolia to the shadows of Altai mountains. Turks changed their land, religion, alphabet and even the whole life style throughout their history but their love and obsession for archery remained until the beginning of 20th century. Among the three stages in that Turkish archery can be examined, the best known one was the post-Islamic stage. Especially the Osmanli (Ottoman) archery was very well documented with numerous treatises, tekke[1] registration books, menzil stones and collector items in museums’ and private collections. Turks adopted Islam in early 11th century and Seldjuk Turks entered Anatolia by defeating the enormous Byzantian army under the commandement of Roman Diagones IV in Manzikert (Malazgirt), in 1071. Probably the Turkish army included other ethnic groups, which was supposed to be a natural result of nomadic life style and culture[2]. It must be expected that the weaponry was not homogenous neither. However some reliefs and pictures indicate that Seldjuks used “Eastern Turkestan type” bows as mentioned by Yücel[3]. This bow type, revealing a recurved design with rigid tips, called “siyah” or “ear”, is similar to Mongolian bows in shape. Additional to the shorthened overall length of the bow that makes it more comfortable on horseback, this Asian invention[4] provides some mechanical advantages. First of all, the early draw weight is higher than that of straight-limbed bows. It results more stored energy in the same poundage and same draw length. Secondly, the leverage effect of siyahs avoids the stacking problem of shorter limbs and allows longer draw lengths. Like all the other Asian bows these were composite bows too and consisted of wood, sinew and horn. These three materials are glued to each other by using collagen-based glues derived from animal tissues. It’s quite possible that other Asian style bows too were used by Seldjuks. There is an old picture of a Seldjuk atabeg[5] Bedreddin Lulu in Kitâbü’l-Agânî, written in 1218-1219, showing the atabeg holding a shorter bow with no siyahs[6]. But unfortunately there is no strong evidence like remained bows or other archaelogical findings. All the other picures of the same time era prove that the rigid-tipped longer bows were more common. It’s obvious that the artistic description of bows and other equipment is severely effected by the common artistic styles of the time as well as the individual approach and skill of the artist. Anyway, the archery equipment has been gradually developed within time and the Osmanli (Ottoman) bows are widely accepted to be the “ultimate bow” of the Asian school.

There are many bows, arrows and other archery tackle in museum collections, the richest one possibly being the Topkapi Palace Museum. Türk Okçuluğu (Turkish Archery) by Dr. Ünsal Yücel, a book that is based on a detailed research on this collection is a masterpiece and includes many aspects of Turkish traditional archery. The author has read all the available texts as well and combined this knowledge with the results of his examinations on the items. Military Museum in Istanbul has an archery section too and other than a few very impressive bows and arrows, tools for bowyery and arrowmaking are also being exhibited. I was lucky enough to make a little research on the collection of Istanbul Military Museum under the kind permission and co-operation of Headquarter of Turkish Armed Forces. Another occasion was accessing the depot of Topkapi Palace Museum as an accompanion of Mr. Adam Karpowicz. He is a renowned bowyer and researcher with an exceptionally fine and scientific approach to the issue. He’s got an official permission from the Minister of Culture to make a planned research on the bows in Topkapi Museum and completed his 5-day work in October 2005.

The Turkish researchers of rebuplic era (since 1923) are not too many, probably because of the lack of practitioners since the closing of tekye-i rumât (tekke of Shooters) by law in 1925. A nation whose ancestors have written their history with bow and arrow has had the chain of its archery tradition broken. Some serious research and publications in late 30’s are followed by Yücel’s work only.

For the last few years Turkish traditional archery arised on its feet again. Beside the new publications, new enthusiasts join day by day to learn the ancient shooting technique. Thanks to the available written sources, the authentic training/education methodology is clear and it will take only time to re-establish the ancient system. The solution of the problem that traditional bowyery got lost too, will certainly be a matter of time. There are only two amateur traditional bowyers today but they sure will be more in number. Nowadays we’re equipping the trainees with very well-built Turkish bow replicas made in Hungary from synthetic materials.

Turkish archery is the last step in Asian archery tradition. The tackle and technique is not too much different, may be a little bit more advanced.

Tackle

Bow

Pic 1: A beautifully decorated bowgrip or “qabza”. Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul

Turkish bow is the shortest among all the Asian composite bows. Only the Korean bows are similar in length and design. Although the siyahs have dissapeared within time, the differentiating cross-section of the limbs along their length and the recurved tips give all the common mechanical advantages of Asian style bows. Moreover there is a strong reflex that differs Turkish bow from its cousines. Shrinkage of the sinew on the back of the bow causes this reflex which is intentionally increased by the bowyer by binding the tips to the grip. The reflexed limbs increases the early draw weight dramatically with an additive –if not synergist- effect to that of recurved tips.

Pic 2: Two unstrung bows in Topkapı Palace Museum.

Turkish bows are so short and tiny that one wouldn’t believe that they were made in enormous draw weights. In the recent research of Mr. Adam Karpowicz the draw weights of some original bows were estimated to be over 130 pounds. With their shorter and lighter limbs their effieciency is much more higher than that of the best selfbows of the same draw weight. Good selfbows are known to launch heavy projectiles to long distances and their efficiency gets higher with the increasing weight of the arrow. Interestingly Turkish bows have a “non-selective” efficiency. It means they launch both heavy and light arrows very fast with incredible percentage of transferred energy to the arrow[7]. So, with very little modifications in its design, these bows could shoot both heavy war arrows to pierce the enemy’s armour and light flight arrows to reach distances over 800 m.

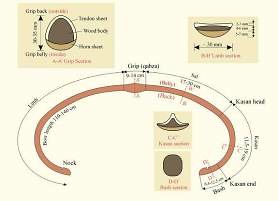

Pic 3: The cross-section of Turkish bow (courtesy of Dr. Mustafa Kaçar)

Besides, the arrows in the museums reveal that even the relatively “heavy” war arrows were not too heavy compared to i.e. English war arrows (Please note that the bows were comparable in their draw weights). Turkish composite bow is capable of piercing the best plate armours with super-fast projectiles from shorter distances. Physics dictates: Lighter arrows fly fast, carrying high amount of kinetic energy, but their speed decrease dramatically in longer distances. In fact, this feature fits perfectly the needs of Asian style warfare since the composite bow was an amazing offensive weapon in the hands of the horseback archer. The “attack and retreat” strategy was accompanied and supported by the incredible skill of the nomadic horseback archer who shot arrows to any directions, even backwards at the chasing enemy, of course from relatively shorter distances. English longbow –as the typical representative of perfect selfbow- was a defensive weapon and used for hitting as many enemies as possible while they were approaching.

Turkish composite bows are little power-packs and require high skill of crafting and highest quality of materials. The wood core was mostly made of various maple species (Aceracae). For sinew backing, the leg tendons of oxes were preferred and the horn on the belly came from water bufallos.

The bowmaking process can be summarized as follows:

-Shaping the 3 (sometimes 5) pieces of maple and gluing them to make the wood core: Mostly, the two limbs are glued to the grip. -Bending the tips to form the recurves: Ancient bowyers was boiling the wood for this purpose, -Gluing the horn laminates to the belly of the bow (wood core): Both surfaces are vertically grooved carefully with a special tool called “taş’in” (pronounced “tush-een”) so that the glue surface is increased, -Sinew backing of the bow: It takes time to wait for drying of each sinew layer. The shrinkage of the sinew bends the bow gradually to a full circle and bending is aided by tightening ropes connecting the tips to the grip. The bow was being seasoned upto 1 year at this stage. -Tillering of the bow is made by heating the limbs and binding them to special wooden forms called “tepelik”, -Finishing the bow: The back is covered with beech bark, leather or only with varnish in some rare examples. The bows were sometimes decorated with golden leaf and a lyric text. Verses from Qur’an or archery related sayings written by calligraphers[8] were not rare. Nearly all of the bowyers signed their work too.

The bow lengths were 90 cm–134 cm and the profile in unstrung position slightly differs in different type bows. Each type were thought to be ideal for another purpose, i.e. target, war, flight, etc. The surface finish is determined by the bow type as well. The flight bows were covered by beech bark, called “toz”, enabling the bow to be conditioned with heat prior to competitions. This process, called “timar vermek”, was accomplished by putting the bows into special conditioning boxes for 48 hours. The boxes were left in rooms upstairs of ovens for a slow release of all the humitidity in the bows. As a result of timar the physical weight of the limbs decreased and the bow’s draw weight increased. Less limb weight means higher efficiency. With the increasing draw weight, the performance of the bow went dramatically up. The sinew backing of the so-called ”tirkesh bows” (war bows) were protected by a thin layer of horse leather for maintaining their performance under inconvenient weather conditions. This very thin, flexible and tough leather came from the back of the horse and was protected with an oil-based mixture called “sandalos revgânı”.

The string was made from different materials by arcaic Turks whereas Osmanli bowyers preferred raw silk. Special loops (tondj) were knotted to bind the string to the bow nocks.

Arrow

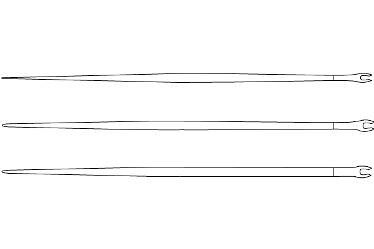

Turks have used barelled wooden shafts with special profiles called “endâm” (pron. “and-um”). There were three profiles and each were preferred for different purposes. While war arrows were mostly in tarz-ı has shape, flight arrows were mostly made in şem endâm (sham and-um) and target arrows in kiriş endâm (kee-resh and-um). Flight arrows in tarz-ı has (tarz-i hus) shape were not rare neither.

Pic 4: Profiles of Ottoman-Turkish arrow shafts: sem endam, tarz-i has, kiris endam

All metal arrow points are generally named “temren” and all they were inserted into the shaft. The neck of the shaft adjacent to the point was reinforced by either sinew or rings made of bone. War arrows were tipped with broadheads and some of the heads were narrowed and thickened like a bodkin to attack the armoured enemy. Target points were made of metal and looked very similar to modern versions with their typical bullet shape. Inspiring from their similarity to olive in shape, they were called “zeytûnî temren”.

Pic 5: Flight arrows with ivory “soya” tips (Private collection of Prof. Dr. Metin Orhan-Photograph: Fuat Ozveri).

There were several types of flight arrows with different profiles, points, fletching and nock style. Most of the flight arrow were tipped with ivory or bone points, called “soya”. The connection of soya to the shaft was “glue on” type: The shaft end was tapered and the point was glued on it.

Turks have used three types of nocks. Selfnocks were rare and only used at low quality war arrows. High quality flight and target arrows were finished with “başpâre” or “bakkam” gez. Başpâre was a one-piece nock made of horn or bone and was very similar to today’s plastic nocks. Bakkam nock however is very typical and unique. They were made of a harder wood, shaped as two seperate lips and glued to the tapered rear end of the arrow shaft[9]. Then they were wrapped with sinew that was soaked in hot fish glue. Anyway, the strike of the string was faced by the arrow shaft.

Like the arrows of other Asian and Middle Eastern schools, longer feathers with lower profile were preferred as fletching but there was an exception. One of the flight arrows, the so-called “pishrev arrow” had shorter fletching with higher profile.

Turkish arrows are short which indicates a shorter draw. The flight arrows are even shorter but were mostly shot with an over-draw, called “siper”.

Technique

Draw

Turkish archery is an extension of Asian school and so is the shooting technique. It does not differ too much from other styles using thumbring, except the shorter draw. While many Asian schools like Korean and Mongolian swear for longer releases, Turkish bows were probably drawn to 28-29 inch which is indicated by the relatively shorter arrows, old pictures and some rare photographs. Still it makes sense to believe that it was up to the decreasing length of the bows within the last few centuries. It’s known that some Turkish treatises[10] and Busbecq[11] reported the Turkish draw to be longer, reaching the ear. Turks in pre- and early Islam era might have used a longer draw.

Pic 6 a,b: Turks might have used longer draws (a) but the late Ottoman’s draw was certainly shorter (b), the anchor being somewhere at the corner of the mouth or a bit further.

Thumbrelease

Turks have shot with thumbrelease like most of the nations of Central Asian origin. Mostly a thumbring was worn to protect the thumb and aid the draw. This release was named by Edward Morse as “Mongolian release”. Some experts believe this term to be irrelevant and a result of discriminative tendencies among European intellectuals in the early 20th century[12]. Since this draw has been used by many other nations and tribes other than the Mongols, even by some African and North American natives, contemporary authors prefer a more convenient term like “thumbrelease”.

Drawing and releasing the string with the thumb causes a different “inner balistic” which supposedly gives the arrow more speed and flight stability. The archer’s paradox occurs towards the opposite direction and that’s why the arrow is shot off from the “opposite side” of the bow. Yes, the arrow rests on the thumb of the bow hand. This may sound weird to the archers who are used in the 3-finger release but when examined in details some additional advantages of this technique would come out.

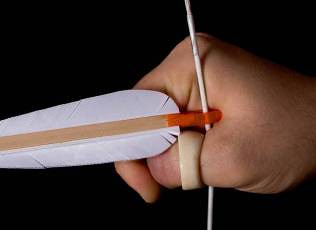

Pic 7 a: The arrow rests on the knuckle of the thumb and is shot off from the“opposite side” of the bow. Pic 7 b: The “lock “ or “mun-dull” as applied by Otoman archers.

While the string is loosed it “rolls” on the narrow edge of the thumbring –if any used- and the arrow shaft doesn’t bend as much as it would when released with three fingers. The release is sharper and cleaner than 3-finger release. Although this feature does not completely eliminate the need for a proper spine size, thumbrelease shooters worry less about the perfectly matching spine. If thumbrelease is mastered, the bow digests shafts of a wider spectrum of spine. Since the stored energy is not wasted by the bending shaft the initial velocity of the arrow is higher.

This technique enables a higher shooting sequence too since the archer nocks the first and the following arrows from the right side of the bow (for right-handed archers). A well-trained archer can shoot the first and the two following arrows very fast, especially when he holds the second and third arrows in his right hand.

Pic 8 a-f: Nocking the first three arrows from the right side of the bow and shooting with the thumbring provide very fast shooting sequence and comfort, especially on horseback (Photographs: Fuat Ozveri)

The last but not the least, the special locking of string hand (mandal, pron. “mun-dull”) helps holding the arrow during the draw. The index finger should press the arrow shaft gently to the bow. This stability gives the archer fascinating flexibility and enables him to shoot in any positions on horseback or on the ground.

Pic 9 a, b: The short overall length of the Turkish bow and thumbrelease give the archer great flexibility to be able to shoot to any direction and nearly in any position, even lying back (Photographs: Fuat Ozveri).

Thumbring (zihgîr or şast[13])

Although it’s known that leather rings were widely used in the army there is no single sample remained to these days. Still there are many samples in museums’ collections proving that rings were mostly made of semi-precious stones, bone, ivory, horn and various metals. Osmanli archers mostly preferred ivory because this material was well polishable and long-lasting. Turkish rings have a thumb pad that protects the thumb from slapping of the string and in some rare examples the ring was richly decorated with engravements and inlays of precious stones. Whether they were functional archery tools or carried as a status symbol must be researched.

Pic 10 a: Thumbrings made of modern materials. From left to right: phenolic resin, acrylic resin, plexiglass. Pic 10 b: Thumbring of Yilmaz Cebecioglu, a friend of author. It’s made of silver and semi-precious stones.

Many enthusiasts claim that the best way shooting with thumbrelease is without any ring. It’s clear that drawing heavy bows without any aid would not be possible.

Pic 11: Sultan “The Blond” Selim (Selim III) shooting at hand-held puta. The artist captured the moment of follow-through with great success: The string hand with the thumbring is still swinging in the air, the feathers in Sultan’s turban are waving and the concentration of the sultan can easily be seen in his face (Hünernâme, 16th century, Library of Topkapi Palace Museum).

Siper

Siper is probably the first over-draw in the history. Wrapped on the bowhand’s wrist and thumb this device provides a longer draw with shorter arrows. Despite the possibility that it was used for target shooting as well, its main purpose was drawing shorter flight arrows further. Shorter arrows were lighter in weight and higher in spine which means a higher initial speed and a longer distance. According to Yücel[14] siper must be accepted as a sign of degeneration in Turkish flight archery. His argument is that the record distances over 800 m were reached in 16th century, a hundred years before siper came into use.

Pic 12: siper or bilek siperi

Pic 13: “Siper” served as an overdraw and enabled the cam-un-cash to shoot shorter arrows with less weight and greater spine. Here is a modern replica with a regular target arrow, just for demonstration purposes.

Turkish traditional archery is unique with its institutional aspect and represents the peak of Asian school with its tackle. After many years of interruption this tradition started to breath again. I hope that there will be more and more people in Turkey and abroad who will be aware of the cultural and technique wealth behind Turkish traditional archery. [1] The place where systematic archery education was being given. Tekke was not too different than the modern sportsclubs except the prominant mystic atmosphere and influence. [2] It’s a shame and mistake of historians to categorise nomadic armies according to the tribal identity of their warlords. Even in Chengis Khan’s army there were thousands of non-Mongol groups, including Turks and even Chinese. [4] Siyah tipped bows are widely spread in Asia: Hun, Magyar, Avar, Mongol and Seljuk bows, to mention a few. [7] The efficieny is measured as the percentage of the energy transfered to the arrow. Heavy arrows are absorbing more energy so all bows, including Turkish bows are more effiecient with heavier arrows. But the difference of [8] Turkish caligraphy is another traditional art which fortunately survived. Because of the Islamic restrictions in drawing/painting most of the living creatures, “hüsn-i hatt” (beautiful writing) was highly developed and widely used for decoration purposes by Ottomans as well as the other Islamic countries.  |